Your basket is currently empty!

Natural blue: Salt and fresh indigo leaves

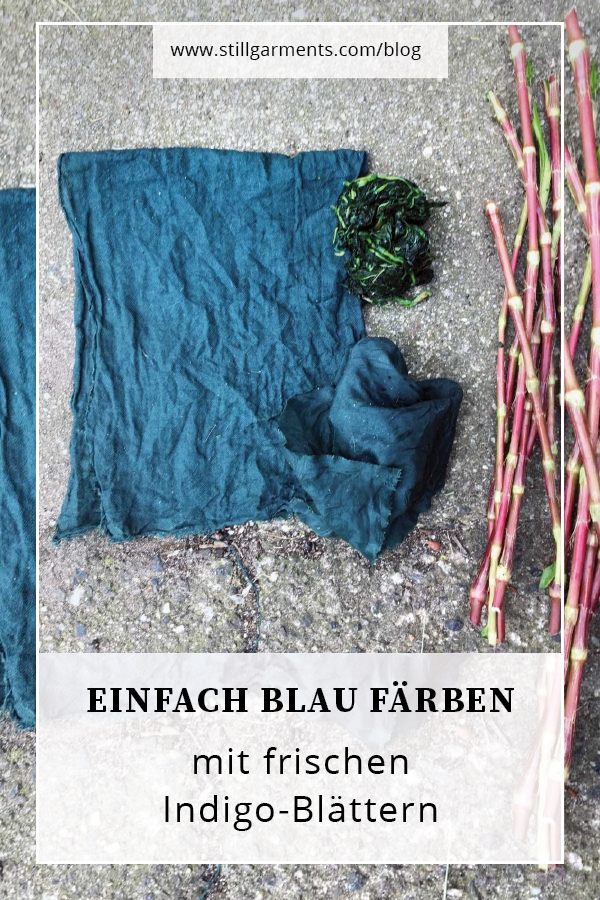

Diese Methode zum blau färben mit Indigo ist mir inzwischen besonders lieb, weil sie so zugänglich ist. Ohne viel Zubehör kann ich direkt von den Pflanzen im Garten das Indigoblau aus frisch gepflückten Blättern kneten. Am besten funktioniert es mit den frischen Blättern vom Dyer's knotweed (auch Japanischer Indigo), Polygonum tinctorum,. Aber auch mit woad, Isatis tinctoria, and achieved beautiful colors, albeit lighter and more greenish. All it takes is a small amount of salt and the fabric. Compared to the various indigo vats that are used to dye blue, this is a lot simpler.

(Möchtest du lieber das blaue Pigment aus Pflanzen zu gewinnen? Das geht auch, und ist etwas komplexer.)

A Japanese craft, travelling the world

I think the first time I saw this method was in one of my favourite online spaces – a Facebook group of all things! „Indigo pigment extraction methods“ I highly recommend to join the group if you want to grow any indigo plant. A global community sharing experiments, learning, questions. The group is brillant! Whether you are gardening in pots or in a large field, here you will find others who are trying the same, helpful documents and a place for questions that might arise. The group was founded by Brit Boles, also known as seaspellfiber on Instagram.

So that's where I first saw this video, of a Japanese indigo dyer, and her demonstrating this "salt rub method". The dyery, Ohara Koubou, is located north of Kyoto.

How to dye blue with indigo and salt

This method works best on animal fibers such as silk and wool. You can pre-treat vegetable fibers with soy milk if you want to dye them using this method.

Pick the leaves - for a strong color it should be at least twice the weight of the fabric in leaves. Work as quick as possible. This method works thanks to enzymes in the leaves, which are broken down by heat over time.

I tear the leaves once and start adding a tablespoon of salt. Now the leaf mass is kneaded with the salt until more and more liquid comes out - depending on the amount of leaves add a little more salt. Then add the fabric (previously soaked in water and squeezed out) into the mass and massage the liquid into the fabric. When you're dyeing wool, rubbing it can felt the fibers. In that case, just gently knead the liquid into the fiber.

Depending on the time of harvest and the fiber, the hues vary from blue to more turquoise-green tones. My dye results with woad leaves were particularly variable - I only got real shades of blue with the dye knotweed. If you want to dye a more "typical" indigo blue, I'd recommend vatting your indigo.

But you can also use the salt method for deeper shades. To do this, overdye several times. However, you will need fresh indigo leaves for this, unlike a vat, in which you can dip your fibers repeatedly.

I hope give this method a try! I look forward to the time the plants are ready for it every year.

Local colour, global context

I think it's great and important to experience dye plants in a very local and accessible manner. Gardens and even overlooked backyards are so valuable to enable that. And it's so very empowering to be able to dye textiles ourselves with means that are understandable and tangible. For me, this is a very important part of a sustainable clothing culture. At the same time I ask myself more and more – where is the line between appreciation and cultural appropriation is. In this case, too. (There are many interesting thoughts on this tagged with #decolonisethegarden on Instagram.)

The spreading of plants to other places is “natural” and part of their survival strategy. There is also a long history of people who cherished, cultivated and took plants with them and thus spread them. But I want to look closely: How easily is the reality of colonization re-told and made invisible. Like the rest of our world, our gardens would look very different without the extraction of anything deemed valuable by colonizers. Who not only trafficked enslaved people, goods, wealth, foreign plants, but also the idea that the world is their (or our, as I am a white woman) garden, in which they can help themselves to anything. Unjustly, in this image, only some are allowed to help themselves, and others have to to plow, to tend the garden. Cultur, craft, religious practices are part of the self-service buffet. This self image is deeply rooted and practically wears a magic hat to be invisible - that's why I didn't even notice it for a long time. All the more reason to take a closer look now. Do you have any thoughts on that?

To conclude, I want to recommend a book. This is for you if you want to work with fresh indigo: ohn Marshall's „Soulful Dyeing for All Eternity. Singing the Blues“. Es lohnt sich wirklich, auch wenn der Import nicht günstig ist. Ein tolles Buch!

Und wenn du lernen möchtest, mit Indigoküpen Blau zu färben, das kannst in Indigo Intro- lernen.

Comments

2 responses to “Natural blue: Salt and fresh indigo leaves”

-

Mich interessiert, ob es auch schon Erfahrungen mit der Salzmethode von Waldbingelblättern gibt. Ich habe eine gute Stelle gefunden, um ausreichend frische Blätter zu ernten. Leider war mein Versuch die Blätter mit Essig zu verarbeiten, wie es bei Färberknöterich prima klappt, nicht erfolgreich. Ich habe auch von Färbeversuchen mit Waldbingelkraut im Kochtopf gehört. Dazu konnte ich aber kein Rezept finden.

Vielen Dank schon vorab für neue Rechercheergebnisse.

Viele Grüße von SchmetterlingPS es sollte alles in Richtung Blau- oder Grünfärben gehen 😉

-

Hallo,

und danke für die Frage! Da habe ich mich erstmal etwas eingelesen.

Ich habe noch nie mit Wald-Bingelkraut (Mercurialis perennis) gefärbt, und es ist mir auch so in Färbebüchern nie untergekommen. In H. Schweppes ‚Handbuch der Naturfarbstoffe‘ habe ich es mal nachgeschlagen – dort findet es sich auch not, aber ein anderes Bingelkraut, Mercurialis leiocarpa, das auf mit Alaun gebeizter Wolle blau färben soll.

Diese Pflanze ist hier aber nicht heimisch, sondern in Korea, China, Japan.Die Salzmethode ist ja sehr speziell, und funktioniert beim Färberknöterich eben nur, weil er die Indigovorstufe Indigotin enthält, und dazu Enzyme die beim Färben mit den frischen Blättern helfen.

Da würde ich mir vom Wald-Bingelkraut also nichts erwarten.

-

Leave a Reply